MADS GAMDRUP

MADS GAMDRUP

28.05.21 – 16.07.21

It is our pleasure to present Mads Gamdrup’s 5th solo exhibition at NILS STÆRK

How do we perceive color? It is the characteristic of visual perception described through categories with names such as yellow, green, red. The perception of color derives from the stimulation of photoreceptor cells, in particular crone cells in the human eye, by electromagnetic waves radiating between two surfaces. Yet, this technical description does not explain the memory of a specific color when reminiscing a specific evening by the countryside, how we experience colors differently or even that we see colors in our dreams.

In a series of new paintings, Mads Gamdrup continues his lifelong occupation with color research yet moving into a radically new direction both formally and visually speaking. Each painting elaborates on Gamdrup’s interest in monochrome color and its artistic potential in relation to phenomena such as materiality, both physically and psychologically. Working with raw color pigments in the extended field of contemporary art, color can be perceived as a material substance with abstract qualities, giving the pictorial expression a spatiality that opens up, allowing for an individual interpretation.

-

Photography is Painting with Light. Mads Gamdrup’s New Works

Mads Gamdrup (b.1967) has been working with photography for three decades, but in this exhibition he shows monochrome painting. The step from photography to painting is radical but, in relation to Gamdrup’s artistic practice, also logical. The question raised is: ‘How much light does colour absorb?’ The preoccupation with the impact of light on our vision has been central to his work with photography; now he uses painting to answer the question.

Colour and light

The word ‘photography’ derives from the Greek phos, meaning light, and graphō which translates as writing, drawing or painting. If we look at the meaning of the word photography, we understand how crucial the question of light and the experience of colour is for photography, and also how it can lead to painting and to expressing oneself in colour. Photography is, in other words, painting with light.

Light is crucial to how we perceive colour. Aristotle (384-322 BC) in his time was already able to state that ‘Light is what makes objects visible to us’, but the fact that the perception of colour differs under different lighting conditions, and in different individuals, is something that still puzzles and interests scientists today. We might argue that the sky is blue, but is it actually? How colour appears depends on the lighting ratio at a particular time, yet we see the sky as blue because that is what we expect it to be. There are both physiological and psychological and, we might add, cultural variations in the way colour is perceived. Goethe (1749-1832) even thought that ‘colour theory is an interdisciplinary area of knowledge involving research in physics, chemistry, biology, physiology, psychology and art.[1]’

If we look up colour in an encyclopaedia, we can read that it is a ‘... physical and material property of objects which is related to their interaction with electromagnetic radiation.’[2] Newton (1642-1727) was the first to demonstrate that light waves are refracted differently in the transition between air and glass. He passed white light through a prism and found that it separated into a spectrum of colours: violet, indigo, blue, green, yellow, orange and red.[3] In a stricter reality, however, there are only three colours, red, green and blue that the eye can perceive, but when these colours are placed close together, we experience more. Albers’ (1888-1976) studies in particular have established this: ‘The purpose of most of our colour exercises is to prove that colour is the most relative medium in art, that we almost never experience colour as it physically is.’[4] In order to arrive at a system capable of dealing with and describing colour many people have turned to colour theory, that is, the study of the characteristics, use and composition of colour. Newton’s more than three-hundred-year-old observations, and the colour systems based on them, are considered groundbreaking. Goethe, however, questioned Newton’s studies in optics; for him the nature and properties of colours were more important than their chemical or physical composition.[5]

How a colour is experienced in relation to other colours has to do with perception and adaptation to the given conditions. A perfect example of adaptation is simultaneous contrast, or chromatic induction, which occurs when the same colour is perceived differently depending on which colour it is juxtaposed with. If complementary colours are placed next to each other, the transition will flicker. The same effect can occur with other colour combinations, and this has often been exploited by artists. ‘To achieve the effect of a luminous moon [in traditional Asian art] in a landscape, the moon is laid down as a white circle against a grey sky. This makes the moon appear to shimmer with an inner light, due to the effect of the white paint on the grey.’[6]

Painting

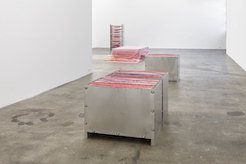

Mads Gamdrup’s new work has a strong physical presence in the gallery space. There are nine large monochrome paintings executed in the traditional technique, which means that genuine colour pigments are hand-ground with raw linseed oil. The paint is applied with both paintbrushes and a broom to the canvas whose dense linen grain has been coated with glue and a number of oil-based gesso layers before being mounted onto a stretcher. The pure oil paints laid onto the canvas with a brush or broom are Dark Burnt Sienna, Indian Red, Primary Yellow and Chrome Oxide Green.

The term monochrome should be understood literally, as only one colour was used for each painting, which is not usually the case, not even with monochromes. The paint has clearly been ground so as to achieve as much texture and pigment saturation as possible and, combined with the repeated long brushstrokes, the paint gains texture and variety. The beauty of oil paint is that it can be applied so that it is either opaque or transparent, pastose or thin, depending on how much linseed oil is mixed into the paint. If only one colour is used, it is essential that it should be capable of evoking both depth and lustre as well as changing hues, which occur when light is refracted in a painted surface. Untitled (CF035313), 2021, is an example of a decidedly colour-heavy painting where the artist has used the linseed oil sparingly, working mainly with impasto but also with more thinly coated and glossier sections, contrasting matt with gloss in distinct layers.

Photography

Gamdrup’s artistic research has largely been about what colour is and how it works in different constellations. Already his early large-scale landscape photography presented an investigation into light and colour, but he found that the interest of the viewer and the discussion got stuck in the purely representational aspects. Observation led to a distancing away from the subject, a greater awareness of how light controls our perception and a conscious unravelling of the image.

The work series 21.06.99 and 21.06.01 indicate dates of the summer solstice. This is the time when the Sun reaches its greatest declination -- angular distance from the celestial equator -- and its highest point in the sky in the northern hemisphere. This is therefore the longest day of the year, and north of the Arctic Circle there is midnight sun. On this day Gamdrup was in Lofoten, Norway. He decided to set the camera’s shutter timer for 24 hours, resulting in nine shots in which small changes in weather and sea level could be observed. Exactly two years later the same 24-hour photography session was repeated in the southern hemisphere, in Harare, Zimbabwe. At this point in time it is the shortest day of the year there, and this same year also saw a solar eclipse. The comparison between the two photography experiments, whose results were almost negations of each other, showed how light controls colour.

The desire to conduct a thorough study of the conditions of colour and light led to the work Monochrome Colour Noise, which is actually a technique for manipulating the unique properties of colour. This is achieved by creating varying degrees of transparency within the individual colour units, from pure colour to pure light. The work consists of colours derived from the torrent of colours accumulated over the years as the artist transferred his own analogue photographs to digital format, which were then transferred to photographic paper in the form of abstract stripes and dots. This technical point of departure for the photographic image may be regarded as a major step away from earlier productions, but Monochrome Colour Noise is still photography. With his subsequent productions he has abandoned photography entirely for painting, at first on glass. The glass paintings consist of stained glass that has been rolled out to form the background of a centrally placed circular field painted with acrylic paint. The glass maintains the transparency of the photograph, whereas the acrylic paint is pastose and impermeable. The works are framed and deliberately bring to mind those of Albers, which in turn refer to Goethe’s more experiential colour studies. These works give a clear indication of Gamdrup’s further research.

Painted colour

The paintings in the new series may seem a far cry from earlier, technically accomplished, large-format photographs of still, bare landscapes and environments in intense colours. These photographs are part of a tradition of Straight Photography, in which the subject is rendered without manipulation. The negative may not be cropped and advanced darkroom techniques are used to achieve an aesthetic characterised by sharpness, high contrast and rich tonality.[7] Straight Photography refers to photography that renders a subject in sharp focus in accordance with the qualities that distinguish photography from other visual expressions, not least painting. The world should be represented as it really is.

This reporting quality of uncompromising objectivity and avoidance of distortion, a striving for technical objectivity in the work, is also present in Mads Gamdrup’s new work. It is not only painting in a more general sense, but also a new and ingenious method in the continuing study of how much light colour can conceivably contain.

Åsa Nacking

Åsa Nacking (b.1963) is the director and artistic supervisor of the art gallery Lunds konsthall. She previously worked for the Rooseum Center for Contemporary Art Malmö; the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art and Moderna Museet Stockholm. She is an art historian and holds an MA in Visual Culture from Lund University and a curatorial degree from De Appel, Amsterdam.